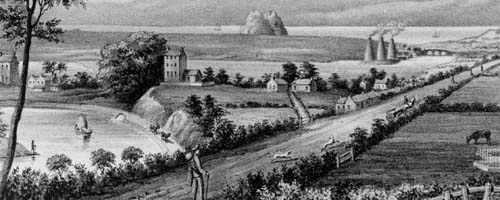

South end of Renton in the 1790s. The Smollett Monument is on the right, the kilns of Dumbarton Glassworks in the centre, and Dalquhurn House on the left. The printfield would be further to the left.

For almost 250 years the River Leven was one of the world's leading producers of bleached, dyed and printed cloth, rivalled only by Lancashire in the British Isles. It concentrated on the finishing processes and would buy in ready-woven flax or cotton.

Early days

Dalquhurn Works about 1930

The first bleach field was at Dalquhurn, set up by Andrew Johnstone in 1715 with the help of subsidies available for the improvement of Scottish manufacturing and trade after the Treaty of Union of 1707.

Flax was spun into thread and woven into linen and later cotton fibres were similarly spun and woven to form cotton. The resulting cloth was woven in Lanarkshire mills and arrived at the Dalquhurn works in an unwashed and unbleached state.

The fields around the Leven were ideal for bleachfields as the river was both clean and fast flowing. Channels were dug to allow the water to flow into the fields. Beech hedges were grown along the fields so that the wind could not catch the cloth and blow it away. The cloth was laid out on the grass and was coated with sour milk. It was slunged with water from the channels to keep it wet. One of the fields now part of the Vale of Leven Golf Club course was called the "slunger" until very recently, Northfield Road being commonly "Slunger Hill Road". The effects of the milk, water and sunlight bleached the cloth, this process taking about four months.

The layout of the drainage channels and hedges was designed by James Watt's uncle John Watt, surveyor and cartographer.

Many books state that Dutch workers helped design and work the fields in the early days, but give no proof. Presumably flat Holland had many similar bleachfields; certainly the Cardross parish register, which covered Renton, has an entry June 16 1728 Anna, natural daughter to Corstian Vanderhydea and Aiken Boury in Dalquhurn was baptized. Natural indicated the parents were not married.

At this time the Leven valley had few inhabitants and seasonal workers came in from Argyllshire to work in the summer bleachfields.

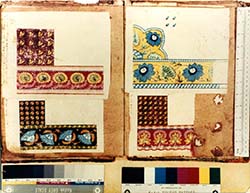

Leven Printfield, Alexandria, pattern book designs for shawls

1794-1800

In 1728 Surgeon William Stirling, father of the Walter Stirling who founded the Stirling Library in Glasgow, bought Johnstone out and established the Dalquhurn Bleaching Company, by which time the fields amounted to more than twelve acres.

As the century wore on chemicals such as sulphuric acid (Vitriol) were introduced, glass carboys of the dangerous liquid dragged toward the fields in rickety carts. Henceforth it was not necessary to use sunlight and bleaching could go on throughout the year, both indoors and out.

The import of printed and dyed cottons from the East was banned in an attempt to protect native industries, but heavy taxes imposed on linen and cotton dyed in Britain in an attempt to protect the established wool and silk industries worked against this, forcing linen and cotton prices up to cover the tax increases.

Nevertheless progress could not be stopped. The expansion of trade with America increased the amount of cotton available, and cotton took over from linen as the more common fabric worked.

Other companies come in

Demand increased for the later processes, dyeing and printing. The first printworks, Levenfield, was set up by Todd and Shortridge and Company in 1768 on a site near the present-day Antartex. The old buildings surrounding Antartex are the 19th replacements for the printworks.

In 1770 William Stirling, a nephew of Surgeon William Stirling mentioned above, moved his printworks from the banks of the Kelvin at Dawsholm, near Maryhill, to Renton where he set up the Cordale printworks. Pollution was already starting to affect Glasgow's rivers, whereas Renton received the fresh clear water from Loch Lomond, and the inhabitants were not used to wages as most of their possessions came by barter, and they would thus work for less money.

The first type of printing to be carried out was block printing. Designs were hand-carved on to a block of wood or were made up of designs in copper inlaid with felt. The block was covered with dye and then printed on to the cloth. Pins at the end of each block allowed it to be placed on a track so that the patterns were correctly aligned. A different block was required for each colour.

Later a method of engraving the pattern on to a copper cylinder or roller was invented. This method soon replaced the block-printing method, although block printing continued to be used for expensive, exclusive orders.

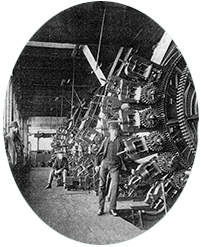

Dalmonach Works photographed in 1867

Printing machines were then developed which could print up to 16 colours, though the Cordale Works only acquired a five-colour machine in the middle of the 19th century, largely because of resistance by the printers fearing that a larger machine might reduce the printers required.

Over the next forty years a number of factories were set up along the Leven at Ferryfield on the Alexandria side of Bonhill Bridge, Levenbank at Jamestown and Dalmonach at the Bonhill side of the Bonhill Bridge. Of these Ferryfield closed before World War I and a catholic school and church were built on the site, and Levenbank was demolished in the 1970s and housing eventually built on the site and Dalmonach was demolished in 2007 for housing.

All had complex histories, Ferryfield Works, for example, having been set up as a bleachfield in 1785, but switching to a calico printing works in the 1830s.

Turkey Red

By the 1820s the Vale of Leven had developed into one of the major areas for bleaching, printing and dyeing cloth, while the Dumbarton Glassworks became the most productive in the country, thus enabling the local area to escape the economic depression of this post-war decade. However what put the area on the world map was the development and use of a fast red dye, one that would neither fade nor run in the wash. It was made from the root of the madder plant and had been used locally since the various works were set up.

Madder had previously been used by the Greeks and Romans and even the Libyans and had been rediscovered in the 15th century by the Dutch. Eventually, in the eighteenth century, French chemists learnt from villagers in Turkey the secret of how to make the dye bright and fast. For this reason it was called Turkey Red.

The process was long and complicated, having 38 stages, taking four months to produce the dye. Rancid olive oil and sheep or horse manure were the main ingredients! Bull's blood was also said to have been used. Some of the processes were for mordanting (literally "biting" in French), preventing the cloth from fading in the sun or running in the rain, i.e. making it fast.

For years chemists worked to identify the chemicals involved and develop artificial ones to take their place.

In 1827 the Croftengea or Alexandria Works, to the south of the Levenfield Printworks mentioned earlier, successfully dyed yarn Turkey Red. Dalquhurn soon followed suit. The success of the process brought rich rewards to the proprietors.

Whether the workers benefited from the Turkey Red revolution is not clear!

Working and general social conditions

Bleachfields and printfields were terms that continued to be used in the 19th century even though the field system had long since given way to the chemical processes of the bleachworks and printworks. Dyeworks seemed to have been always dyeworks.

Possibly because the printfields/printworks were not technically considered as factories and so were not covered by the 1844 Factory Act and missed the protection of the "ten hours bill" which eventually limited hours to 63 and then 58 per week. The workers had a six-day week, with Sunday off. However though the calico printers at Ferryfield traditionally stopped work at 3pm on a Saturday, the exigencies of the Turkey Red process meant that they had to put in a full twelve-hour shift on Saturdays. The normal day was 6am to 6pm with 45 minutes off for both breakfast and lunch/dinner. Children normally worked the same hours as adults.

When trade was brisk everyone had to work whatever hours were necessary, even till eleven or twelve in the evening and sometimes overnight without overtime pay. However when it was slack hundreds of workers would be left unemployed. There was no unemployment pay then, just parish relief.

To cope with the demand for printed cloth there was a great influx of people to work in the printfields/printworks. They came from all parts, from the Highlands, from England and after the Potato Famine large numbers came from Ireland. The technical staff employed in the "secret works" even included French chemists.

Living conditions were poor. Before the advent of gas in the 1830s houses were lit by rush lights and the factories by candles suspended from the ceiling in special tin holders. As late as the 1880s families had to fetch their water in buckets from the River Leven, water polluted by the works, until a Loch Lomond pumping scheme was built. The lades first dug out to divert water into the works to drive the machinery, in the late 19th century were used to produce electricity.

Mid-century developments

The extension of the railways greatly improved the efficiency of the works. The slow shipment of both cloth and coals by barges, here called gabbarts, were replaced in 1850 by trains running initially between Balloch and Bowling to link up with the Forth and Clyde Canal. In 1856 a line was opened to Stirling which was then a considerable port on the Lower Forth. In 1858 the connection was made with Glasgow.

Firms built sidings from the main line into their works and soon coals and cloth from Lanarkshire collieries and mills could make their way direct to the Vale of Leven with no need of transhipment.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1862 the northern Federal states blockaded the ports of the Confederate south, the main suppliers of cotton to Europe. By 1864 supplies had fallen from 172,055 hundredweights to 7,216. The profits of the factory owners plummeted and many workers were made unemployed. It took some time for supplies and profits to be built up, and in this time alternative supplies of raw cotton came on to the world market from India and West Africa.

Further problems arose with the discovering of artificial dyes in the 1850s. Most of the earliest patents were taken out by German firms such as BASF, and the Scottish firms lost their technical leadership.

Mergers

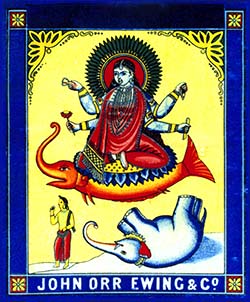

With increased world-wide competition in the finished product market, fanned by Victorian laissez-faire rather than protectionist policy, local firms began amalgamating to increase their efficiency. Around 1860 John Orr Ewing, the man in whose honour the Ewing Gilmour Institute, now Alexandria Library, was erected, amalgamated three works on the west bank of the Leven: the Levenfield works to the north, the Croftengea works to the south, and the Charlestown engraving works in the middle. The works were renamed the Alexandria Works, though commonly styled the Craft.

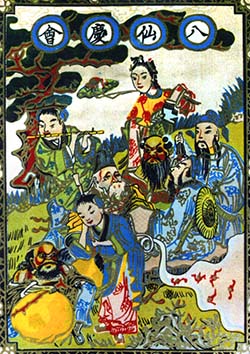

Turkey Red label for cloth destined for the Chinese Market

On the east bank John Orr Ewing's brother Archibald acquired the Levenbank works in Jamestown in 1845, adding the Milton Works in the southern end of Jamestown in 1850 and the Dillichip works to the south of Bonhill in 1866.

The third major block was William Stirling and Sons' works at Cordale and Dalquhurn in Renton. In 1886 the firm finally passed out of the hands of the Stirling family. Two independent factories were also situated on either side of Bonhill Bridge, the Ferryfield works in Alexandria, and the Dalmonach works in Bonhill.

In that year, 1886, the various works employed 7,000 people earning £255 million; they dyed and printed 165 million yards of cloth and even 20 million pounds of cotton yarn. This was exported to India, the Philippines, China, Japan, West Africa, South Africa and Morocco.

These countries however also produced textile goods and it was competition primarily with Japan that forced the three combines to form the United Turkey Red Company in 1897 under the chairmanship of John Christie, who had come to the Vale as a chemist in 1856 and was later to donate the Christie Park to Alexandria.

The independent Dalmonach and Ferryfield works joined the Manchester-based Calico Printers Association in 1899 and 1906.

The 20th century

The amalgamation however was already too late. Other companies had introduced cheaper dyes and more up-to-date working practices. The faster, brighter naphthol red dye was tried but rejected and the older, more laborious paranitranaline, "para", dyes returned to. The Ferryfield and Milton works closed in 1915 with little cloth reaching them to process, though Cordale diversified into making uniforms. The Great Depression caused the closure of the Levenbank, Dalmonach and Dillichip works in the 1930s.

Turkey Red label for cloth destined for the Indian market

On top of this the advent of Ghandi in India brought about a development of their cottage industries and with this the imposition of import duties on finished cotton goods. India had been the major importer of British finished goods, as well as the major exporter of raw cotton. With the independence of India after the Second World War the Indian market collapsed completely. Cordale closed shortly after the War and Dalquhurn diversified into weaving and knitting and set up the Lennox Knitware Factory. The Alexandria Works also diversified into knitwear and introduced screen- and circular screen printing, but global forces were too strong and the works closed in 1960.

Nowadays part of the Dillichip works is a bonded warehouse and the Alexandria works contain Antartex and Loch Lomond Distillery.

A walk along the Leven cycle path, previously the tow path for the horses pulling the gabbarts upriver before the 1850s, reveals the suitability of the river for textiles with its fast flowing and now once more clear, unpolluted waters. The firms came here because the wages expected would be low, and they eventually went bankrupt because of the low wages in other countries.